This is an essay I wrote a year ago in my composition class. I’ve been waiting to find out if it was published in my school’s annual ENG123 collective before publishing it online, but I don’t care anymore. Recently I was invited to take part in the annual girls-only Facebook status update thing, where we post something random like our bra color or our shoe size to (somehow) raise awareness for breast cancer.

This is what I have to say about breast cancer awareness.

—

A recent poll taken by USA Today revealed one in three adults feel that the ceaseless push to support breast cancer leaves other life-threatening diseases in the dust (Szabo, par. 5). I am one of those adults. At the age of nineteen I was diagnosed with a malignant brain tumor. While my peers’ biggest worries were ten-page term papers, mine became the prospect of facing my own mortality prematurely. I searched in vain for a fellow patient to talk to. The leukemia survivor’s friend never got in touch with me. When I signed up for a pen pal my age who’d survived brain cancer, I was paired with two girls who were both born with brain tumors and went through treatment as babies. There is little to offer a brain cancer patient — most of us don’t live five years post-diagnosis, after all. Yet pink is the color illuminating national monuments and decorating everyday household paraphernalia. Breast cancer, the easier to spot, cheapest to diagnose, and more survivable of the two diseases is the one continually hogging the funding and research spotlight.

When it comes to breast cancer, if something is wrong inside, there is generally an indication on the outside (National Breast Cancer Foundation, “Signs and Symptoms”). There’s a lump. The skin is puckered. There may even be abnormal discharge. It’s also possible that a change can be felt. Women are encouraged to start examining their breasts at an early age to know what is normal for them, and to keep an eye out for any unusual changes in their feel or appearance. Doctors also examine them during regular check-ups. As stated by the American Cancer Society, “We don’t know how to prevent breast cancer, but we do know how to find it early, when the chance for successful treatment is greatest” (ABC’s).

Of course, sometimes breast cancer keeps quiet. That’s where mammograms come into play. The x-ray images they capture often indicate if there is cause for concern. They can “find cancers when they are very small, often several years before a lump or change can be felt” and are “quick, easy, and safe” (ABC’s). Women are encouraged to have an annual mammogram starting at the age of forty, when breast tissue begins to become less dense (NCI Fact Sheet, “Mammograms”). Mammograms are relatively inexpensive tests, averaging around one hundred dollars, usually covered by health insurance. In fact, in most states, health insurance companies are required by law to “reimburse most or all of the cost” (NCI Fact Sheet, “Mammograms”). Many women are even able to get them done free of charge— breast health is important.

As with any cancer, breast cancer is an unpredictable and life-threatening disease. It can metastasize anywhere in the body, including such dangerous places as the lymph nodes, the lungs, or — fancy this — the brain. It also takes a tremendous physical toll; chemotherapy can cause lapses in memory (commonly called “chemobrain”) that sometimes last several years after treatment ends. Treatment can also deteriorate the bones, leaving patients with an increased risk for osteoporosis (“Advances,” 10-11). Many women must have one or both of their breasts removed to fully rid themselves of the cancer. Despite all this, however, breast cancer nowadays is a relatively survivable disease. In fact, breast cancer survivors now make up approximately one fifth of the cancer survivor population (qtd. in Nordqvist, para. 2). Certainly this is the result of the tireless effort to find (and fund) a cure.

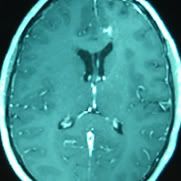

Brain cancer, on the other hand, is a master of disguise. There are no outward signs of this disease. It shares its most common symptoms — headaches, nausea, dizziness, fatigue — with relatively innocuous problems: stress, PMS, and side-effects of numerous over-the-counter drugs. I suffered from headaches at eighteen. I woke up tired every morning. I felt queasy a lot. I was also a senior in high school, balancing homework with late-night theatre rehearsals, eating when and what I could. Headaches run in my family. My wisdom teeth were coming in. My only noticeable symptom, what we’ve come to call “visual anomalies,” saw me to an optometrist for a thorough eye exam. The swollen optic nerves he found landed me in the first of what would become countless MRIs. But I was lucky. Most brain cancer patients don’t discover their own tumor until they have a seizure.

Simple physical tests can indicate if an abnormality exists, but they are unreliable (in fact, when I went to the school physician for persistent headaches, he tested me, and when I presented normal, assured me, “You don’t have a brain tumor” — imagine my relief). The only way to truly discover a brain tumor is to perform an MRI scan of the head. The only way to see a brain tumor clearly is to perform an MRI scan with an injection of contrast dye. These scans are not cheap; on average, a scan of the brain with contrast (which is always necessary) costs roughly $2,500 nationwide (“Compare MRI Cost”). What’s more, getting an MRI approved with insurance companies can be a hassle. MRIs are not encouraged the way mammograms are. There is no recommended age to be screened for brain cancer. But like any cancer, early detection is key to successful brain cancer treatment as well.

Thanks to the blood-brain barrier, primary brain tumors cannot metastasize. This one blessing is small consolation. Brain tumors attack from within the very essence of our beings. Even a benign tumor can wreak havoc if located properly. Surgery can create problems or complicate existing deficiencies. In many cases, due to a tumor’s location, surgery isn’t even an option; the risks outweigh the benefits. Standard treatment works until it doesn’t — for me, that meant less than six months. Brain cancer is aggressive and almost always grows back with a vengeance. The clinical trial chemotherapy I currently take has worked miracles. I am fortunate. The reality is, however, that brain cancer’s prognosis is grim. In the two years since I was diagnosed, three patients I knew lost their battle. Two were my age. The other shared a room with me during hospitalization for our second surgeries. All three declined in health rapidly.

In 2011, it is estimated that 290,000 women will be diagnosed with breast cancer. Of those women, roughly 40,000 will not survive longer than five years — fourteen percent (Breastcancer.org). This means that eighty-six percent of women diagnosed with breast cancer in 2011 will survive the standard five year mark, and this number is increasing every year (Breastcancer.org). The National Cancer Institute projects that approximately 22,000 new incidences of primary brain cancer will be diagnosed this year (“Snapshot”). Comparatively, this is a much smaller number, half of the expected breast cancer mortalities. However, thirty-three percent of those patients will lose their battles before five year passes —nearly twice the amount of expected breast cancer deaths.

Perhaps the reason breast cancer continues to dominate is because it is a “sexy” disease. It infects a very important part of the body — women and men can agree on that. Pink is pretty. Grey is not. There is nothing “sexy” about brain cancer. There are no witty phrases or slogans that will sell on a t-shirt or silicon bracelet. In the shadow of pink, brain cancer is lost.

Each time I go to the National Institutes of Health for my own MRI, I am devastated by the patients that surround me. One processes information on a five-second delay. One can’t remember how she got to the building. Many are incapable of filling out their own simple paper work. Some can’t function independently at all. Each time, my heart shatters for their suffering and for their caregivers’ grief. I cannot fathom the torture of watching a perfectly sentient loved one deteriorate into incoherent shambles — I cannot bear the thought that someday, the incoherent shamble in the corner could be me.

—

Works Cited

– “A Snapshot of Brain and Central Nervous System Cancers.” National Cancer Institute. Oct. 2011. Web. 12 Nov. 2011.

– The American Cancer Society. “ABC’s of Breast Cancer Early Detection.” Pamphlet. American Cancer Society, Inc. 2003. No. 341601-Rev.4/11.

– Breastcancer.org. Breastcancer.org. Web. 08 Nov. 2011.

– CancerCare Connect. “Advances in the Treatment of Breast Cancer.” Booklet. CancerCare. 2010.

– “Compare MRI Cost.” MRI Cost and Pricing Information. Web. 06 Nov. 2011.

– Kuntz, Christopher. “Brain Cancer Survival Rate.” Cancer Center. 3 May 2011. Web. 12 Nov. 2011.

– National Breast Cancer Foundation Official Site. National Breast Cancer Foundation. Web. 23 Oct. 2011.

– National Cancer Institute Fact Sheet. “Mammograms.” National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health. Web. 30 Oct. 2011.

– Nordqvist, Christian. “Breast Cancer Detected From Screening Survival Rates Lower Than Expected.” Medical News Today. 24 Oct. 2011. Web. 25 Oct. 2011.

– Szabo, Liz. “Pink Ribbon Marketing Bring Mixed Emotions, Poll Finds.” USA Today. 07 Oct. 2011. Web. 23 Oct. 2011.